The announcement of the first oil barrels produced from the Sangomar field has garnered global attention, officially marking Senegal’s entry into the league of oil-producing nations. However, the crucial question remains: What will Senegal truly gain from this endeavor?

Understanding the Revenue Sharing Mechanisms

While numerous analyses have been conducted on this topic, many only consider specific parameters. To accurately assess Senegal’s share of the oil revenue, a clear understanding of the governing mechanisms and associated challenges is essential.

Have You Read?

Senegal Joins Oil-Producing Nations with Sangomar Field Extraction

Upon assuming power, the Sonko/Diomayé administration pledged to review the fiscal arrangements surrounding the Sangomar project, aiming to increase Senegal’s share of the oil revenues. Former President Macky Sall acknowledged this as an option but suggested it might be unnecessary, claiming Senegal already secures 60% of the oil rent.

Examining the Sangomar Contract

To gain deeper insights, Ecofin Agency examined the publicly available Sangomar petroleum contract. The focus was on the stakeholders, the initial expectations of the Senegalese authorities, and potential points for renegotiation.

The primary players in the project include Woodside Energy, the Australian-registered exploration partner, now holding an 82% stake after acquiring shares from Cairn and First Australian Resources (FAR). The Senegalese government, through a 10% participating interest in the research joint venture, contributed to exploration costs.

Senegal’s Evolving Stake

The production-sharing contract (PSC) allowed the Senegalese government to increase its stake during the development and production phase, impacting its share of distributable production (Profit Oil) and cost contributions. This stake was subsequently raised to 18%. Consequently, the Sangomar oil exploitation entity now comprises Woodside Energy (82%) and the Senegalese government (18%).

A third player, with passive interests linked to Woodside Energy, emerged when Woodside acquired FAR Limited’s stake. Part of the payment was in cash, with the remaining balance ($55 million) deferred until oil production commenced.

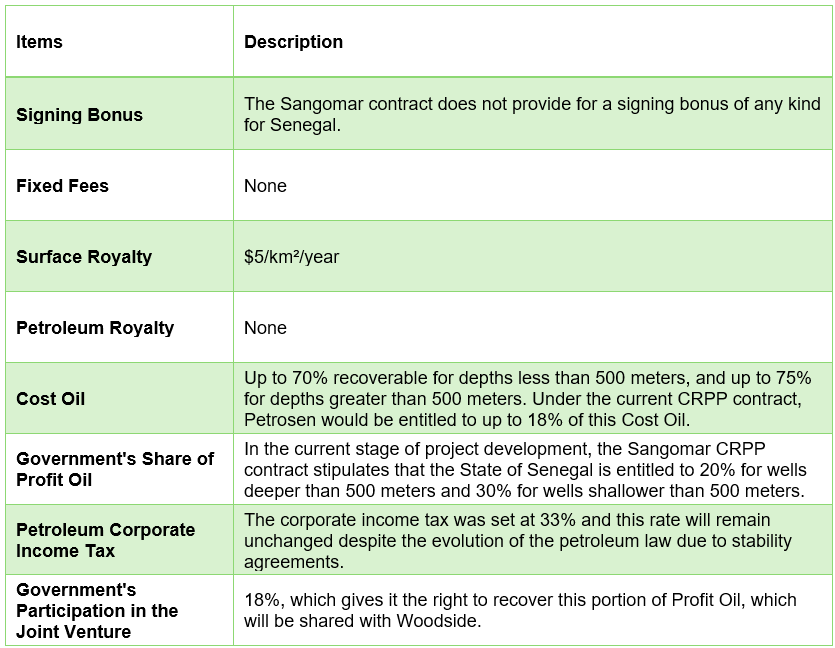

Senegal’s Entitlements

In oil projects, countries often negotiate various revenue streams. These include:

- Signing bonuses: Lump-sum payments for exploration or exploitation rights.

- Fixed fees: Regular payments unrelated to production or profits.

- Surface rentals: Annual or quarterly payments for land use.

- Royalties: Payments based on the quantity of oil extracted.

The remaining production, after deducting fees and royalties, is divided into Cost Oil (covering exploration, development, and production costs) and Profit Oil (shared between Woodside and Petrosen). Additionally, the government levies corporate taxes on oil companies and receives a share of Profit Oil through the national oil company, based on its participating interest in the joint venture.

In the negotiation of the Sangomar contract, Senegal took a notably generous approach with its partners. This generosity later became apparent to the Macky Sall government. While the Sangomar contract itself wasn’t specifically renegotiated, the 2019 petroleum code introduced several key changes.

The revised code now mandates a bonus determined within the contract itself, along with fixed fees of $50,000. The surface royalty also saw adjustments, increasing from $5 per km² per year to a range of $30-$35 per km² per year. A petroleum royalty between 7% and 10% was established, and the share of expenses allocated to cost recovery was capped at 55% to 77% of crude oil production.

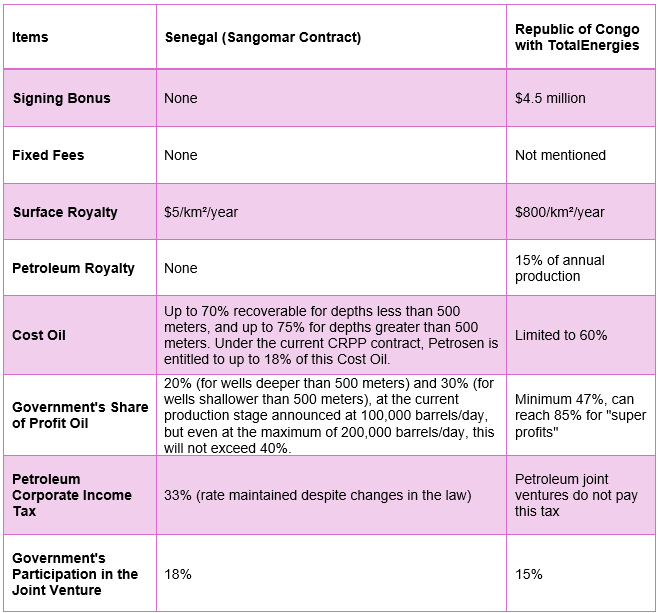

Sangomar: Not Senegal’s Most Profitable Venture

It’s evident that the Sangomar project won’t be the one where Senegal maximizes its oil profits. A comparison with another African oil producer, Congo, highlights the potential for improvement in Senegal’s deal, as suggested by the Sonko/Diomaye team.

In Congo, joint ventures in the oil sector are exempt from corporate taxes, but signing bonuses can reach $4.5 million. There’s a 15% annual petroleum royalty on production, and the share of oil allocated to cost recovery is limited to 60%. The surface royalty is set at $800 per km² per year. When it comes to profit oil sharing, the state secures a minimum of 47%, potentially rising to 85% in cases of super profits.

In addition to potential losses from a less-than-optimal contract, Senegal granted tax exemptions on various equipment for oil development and production. It’s unclear whether these exemptions, essentially fiscal subsidies, will be counted as Senegal’s contribution to development efforts. The contract also gives the operating company leeway in defining the depreciation of its exploration and production costs. This could lead to frequently reaching the maximum 75% cost oil threshold in the early production years.

Petrosen’s High-Interest Loan

To fulfill its development commitments, Petrosen, the national oil company, borrowed the equivalent of $450 million to finance its share. The lender was a Woodside subsidiary, with interest rates ranging from 7% for the production phase to 13% for development. This financial burden could further reduce Senegal’s share of project profits.

The latest environmental impact assessments of the Sangomar project aren’t publicly accessible. Reviewing the environmental management plan is crucial to understand how responsibilities have been allocated.

Re-evaluating Senegal’s Gains

Accurately assessing Senegal’s gains requires re-evaluating the project under current conditions. When the exploitation decree was signed, President Macky Sall approved an analysis projecting a total development cost of $4.2 billion and annual operating expenses of $326 million. Under those conditions, the state’s share over 25 years of operation was estimated at $12.5 billion, with an average oil price forecast of $65 per barrel.

Several parameters have changed since 2020. The project’s development cost is now estimated at $5.2 billion, according to data Woodside Energy provided to S&P Global Ratings. Operating costs haven’t been publicly disclosed, and Petrosen will contribute 18%. The average oil price over the past three years (2021-2023) is around $84. The future trajectory of oil prices is uncertain, especially with Saudi Arabia’s oil no longer pegged to the US dollar.

Limited Room for Maneuver

The current Senegalese government has limited legal recourse. The Sangomar CRPP Contract includes a stability clause, stating that changes to existing conditions at the time of signing don’t apply to the project’s operating partners. Despite a new petroleum law in 2019, the 2004 conditions still apply. Arbitration is an option, but the competent jurisdictions are outside Senegal, and any forceful action could trigger a “force majeure” situation, leading to international litigation.

The government can, however, monitor production quantities and verify that all expenses attributed to project development and operation are accurately measured. This can help prevent unjustified reductions in profits to be shared or corporate taxes. A more transparent fiscal framework, giving the tax administration the necessary control to collect due taxes, is crucial.

Source: Agence Ecofin